I don't pull all-nighters. Anyone who knows me is aware of this. I get tired and hungry and cranky. However, after seeing Prince at the Brisbane Entertainment Centre a week ago and missing the much-talked-about after-party at the Hi-Fi Bar, I promised myself that if, in the unlikely event, another after-party was announced for last night's show, I'd go. Here's how the events of last night (and this morning) unfolded, leading to be stumbling into bed at 5.15am.

7.00pm: Rumours had started circulating that there would be an after-party, and that Prince's management was in the process of securing a venue. Miss P and I joked that it could be at our local, the Prince of Wales Hotel; or, perhaps a little more likely, Eatons Hill Hotel. In the meantime, Mr C goes out to an art show.

8.30pm: DJ Rashida tweets that the after-party WILL be at Eatons Hill Hotel. In the meantime, the hotel tells their Facebook followers that doors open at midnight, and the entry fee is $100 cash.

9.30pm: After much discussion (and attempts to contact Mr C via SMS, phone call and carrier pigeon), Miss P and I decide that we should go. We do, after all, live on the north side of town (the hotel is in the middle of nowhere on the north side). Eurovision semi-finals are forgotten.

10.00pm: I manage to get out of my pyjamas, get dressed, find gloves and a scarf, and walk to Miss P's house. She kindly packs us some pumpkin bread for our handbags in case we get hungry.

10.45pm: We're in the queue outside the hotel with no more than 50 other people. S Club 7 are currently playing inside. There are lots of trashy bogans about.

11.30pm: The last of the S Club trash leaves the venue. Amusingly, some of them make fun of the people lining up to see Prince. The hotel's Facebook page now says that the first 500 people will get in for $50. I finally speak to Mr C. He's going to try and make it.

12.15pm: Mr C is very lost. He's heading home. The venue lets us in. For $50. No more than around 300 people have shown up.

2.00am: We're still waiting. There is soundcheck after soundcheck. Sound dudes are being yelled at. We've resorted to sitting on the floor, and are mesmerised by some Tina Turner lady wearing leopard print shaking her arse in front of us. A creepy young dude who could be her son seemingly wants to bang her. Miss P is munching on her bread.

2.30am: NPG come out on stage. Prince makes a brief appearance. The backing singers inform us that we need to put our phones away. If we do this, they will play until the sun comes up. Prince comes out and jams on his bass. And dances. And sings. And dances. We are in awe.

3.00am: The NPG singers are covering Toto and Extreme. We are singing Extreme's 'More than words' with Prince's band. At Eatons Hill Hotel. In the middle of nowhere. At three in the morning. For $50.

4.00am: We're sitting on the floor again. Prince is on stage, but we are exhausted. We contemplate leaving, as lots of others have already done.

4.30am: Miss P realises that we can stand side of stage and be literally a few metres away from Prince. We are again in awe.

4.45am: We can't do it any more. We decide to leave. On the way out, we realise it's the finale. We stay for the rest. The lights are all on. There are probably 150 people left. Prince appears to give his guitar to someone in the audience. I manage to sneak a couple of photos before it's all over.

4.50am: We're in the car heading home. Miss P is loudly playing Whitesnake to keep herself awake.

5.15: My teeth are brushed, my pyjamas are on, and I'm in bed. I feel sick from tiredness. But I am happy.

The next morning: Mr C is upset that he missed it (as am I). I get up at 9.30am and toast my pumpkin bread. Then I go back to bed. It's now 12.30pm. I'll probably eat some lunch soon, and then snooze away the rest of the weekend.

A platform where I can express my opinion on all manner of political topics — from poverty, racism and immigration to matters of art and culture.

Showing posts with label Brisbane. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Brisbane. Show all posts

27 May 2012

22 January 2012

The state of music festivals in Australia

Today is the day of the 2012 Big Day Out on the Gold Coast. A few internet conversations of late have made me think a lot about the festival situation in this country, so I wanted to share (read: rant) some of those thoughts.

I went to my first Big Day Out in 1999. I remember it like it was yesterday. My dad transported me and two friends down from Bundaberg and drove around the Gold Coast for the day waiting for us. It was the first Big Day Out after the widely reported ‘last ever’ one in 1997. I remember the day with extreme fondness, mostly for the kindness of the punters. Sure, there was the odd weirdo, but the unspoken rule of looking out for those around you was well in force. (I’ll always be grateful for the kind souls who chose to rescue my naive self from the Marilyn Manson moshpit.) That year, I got to see some of the bands that were dear to my heart at the time — Manson (of course), Korn, Hole, and even Fur and Sean Lennon. While I can’t so my love for all of these acts continues today, there is no doubt that I was there solely for the bands. Look, here I am counting down the last day!

The next few years of Big Day Out attendance continued in the same vein — great bands, with an audience of tens of thousands of people who were there to enjoy music with like-minded folks. Sure, it was often a bit of a stressful day dealing with the portaloos (or holding it in!), the heat and the crowds — particularly for those of us not used to the surf culture of the Coast — but it was a positive experience overall. Similar things can be said of the now-defunct Livid festival. Generally speaking, at that time, no-one bought tickets to music festivals unless they were really into the bands.

Fast forward a few years, and things started to get ugly. Livid had its last hurrah in 2003 (and smaller festivals like Summersault hadn’t been around for years). Great bands were still booked for the Big Day Out (Iggy and the Stooges, PJ Harvey, the White Stripes, the Beastie Boys and Jane’s Addiction, to name a few), but by the mid 2000s something had started to change (and I’m not talking about she-pees). As a small female, I no longer felt entirely safe being in the crowd on my own to watch a band. People were getting peed on, puked on, spat on, groped and punched. Very few punters were looking out for those around them; it was every man/woman for themselves. For many people, the bands seemed to be an added extra included in the ticket price.

I’m not sure it’s a coincidence that things seemed to get a whole lot worse after the 2005 Cronulla riots. At subsequent Big Day Outs, I noticed an increased number of Southern Cross tattoos, Australian flags, and aggressive people asking others to kiss said flag. A friend of mine was abused for daring to wear a temporary tattoo of the Aboriginal flag to the Sydney event on Australia Day. Due to factors such as these, I decided that the 2008 event would be my last. Rage Against the Machine was the last Big Day Out band I ever saw, and I’m glad to have ended it this way. (It is unfortunate, however, that a good number of the shirtless, aggressive, sweaty bogans in the crowd seemed to completely misinterpret the intent of RATM’s music.)

While Livid may have closed shop, in the early 2000s new festivals began to emerge. The most notable was Splendour in the Grass in Byron Bay (which has now relocated to Woodford north of Brisbane). While I attended three of these festivals over the years (twice even camping!), the overcrowding and general ‘yuckiness’ eventually started to permeate there as well. Three days of portaloos and rain and mud and no showering gets to you after a while. In addition, while there are often very high-quality international acts included on the bill, I can’t help but think that the event could (with some careful curating) be condensed into a single day with minimal ‘filler’ — thus eliminating the need to camp, arrange costly accommodation or travel long distances several days in a row.

Smaller festivals also began to pop up in the 2000s, with Laneway expanding to Brisbane in 2007. The first festival (in the alleyway next to the Zoo) was a fabulous experience, with Peter Bjorn and John, Camera Obscura, Yo La Tengo and the Redsunband making for an excellent day out. Sadly, the relaxed atmosphere seemed to have been lost by the second Brisbane event in 2008, with music seemingly not being an important factor for many in attendance. Having been jostled one too many times by Rayban-wearing, fluoro-wearing, talking-over-the-top-of-the-music hipsters, we gave up. It was easier to hear Feist from outside the festival gates than it was inside. Laneway has since relocated to a new venue in Brisbane, but I haven’t ventured back — mostly due to the fact that I recognise very few bands on the lineup (and I’m not one attend a festival if I’m not into the music).

Also emerging around this time was Sunset Sounds in Brisbane, another two-day festival. While, like Splendour, this one could also easily be condensed into a single day, it’s held at the Riverstage in the middle of the city —making it easy to come and go with little hassle. I attended my first Sunset Sounds in 2011 in the pouring rain (literally a few days before the river broke its banks and flooded the city), and was lucky enough to see Joan Jett and the Blackhearts, Public Enemy and Sleigh Bells. The festival took a break in 2012, but according to the website will return for 2013.

The 2000s also saw the emergence of Soundwave, a niche festival aimed at fans of metal and hard rock. I attended my first Soundwave in 2010 (enticed by the opportunity to see Faith No More), and I admit that I wasn’t looking forward to the experience all that much (with the idea of returning to a 50 000-strong festival a little hard to stomach). Soundwave proved to be an overwhelmingly positive experience — enough so that I returned the next year. It became clear that you’d have to be a real fan of the music to spend $160 on a ticket to see this number of ‘heavy’ acts; consequently, most of the punters were respectful, the crowd seemed a little older and wiser, and I even spotted some families enjoying the day together. While I’m not attending the 2012 festival (it’s a little too much of a c.1998–99 nostalgia-fest for me), if I’m into the music on a future lineup I’ll be in attendance.

In 2011, I saw a Facebook post that gave me real hope for the future of festivals. A new event called Harvest was coming, and the organisers had somehow managed to convince Portishead (and a heap of other amazing bands) to play. The tagline was ‘A civilised gathering’ — which sounded like it was aimed squarely at me. There was also this:

Given that this would likely be my one and only chance to see Portishead live, and that I was promised a ‘civilised gathering’, Harvest excited me. A lot. I’m pleased to say that I wasn’t disappointed. While I understand that the Melbourne event had some teething problems involving drinks tickets (which doesn’t concern me greatly as I prefer sobriety when watching bands so that I can take it all in with clarity), the Brisbane festival delivered everything it had promised. The lineup was full of quality acts (TV on the Radio, the Flaming Lips, the National, Death in Vegas); there was plenty of space between the stages; the portaloos were kept clean; if someone ran into you, they would stop and profusely apologise; and, most importantly, everyone was there for the music. I had the most amazing festival experience of my life right at the front for Portishead (and, yes, this fangirl got to have a brief encounter with the lovely Beth when she left the stage to greet the crowd), and the whole day was stress free. I left the festival that day with the same feeling I had leaving my first Big Day Out in 1999 — one of pure elation, having experienced something special with thousands of people who all understood.

Some people have suggested that my disdain towards the Big Day Out and other festivals could stem from just ‘getting old’. There are a number if reasons why I think that this is untrue. Firstly, I attended my last Big Day Out in my mid 20s — hardly ‘old’ by festival standards, especially since I’d been getting increasingly pissed off with the experience in the years leading up to 2008. Secondly, I have a number of friends who are a decade or more older and stopped attending festivals around the same time. It’s not an age thing; rather, it’s a fed-up-with-idiots-who-couldn’t-give-a-stuff-about-the-music thing.

It’s clear that changes are afoot for the Big Day Out. 2012 marks the first year without co-founder Vivian Lees. The people of Auckland, Adelaide and Perth got a raw deal with much smaller lineups, and Auckland will be completely dropped from the tour after this year. It seems like the perfect opportunity to rethink the approach and start again. Perhaps another hiatus, like the one of 1998, is called for. As it stands, I’d prefer to pay for a plane ticket to see a sideshow in Sydney or Melbourne than venture to the Gold Coast for the day (because, of course, Brisbane sideshows are never prioritised).

For me, the future of music festivals in Australia lies in the Harvests and the Soundwaves — niche festivals aimed at specific markets of music fans. You know, the type of person who would have to actually be a fan of the bands to even consider shelling out $150–200 for a ticket. Whether my dream for the future of Australian festivals will be realised remains to be seen, but I’d prefer to hold onto this hope rather than simply despair for what used to be.

I went to my first Big Day Out in 1999. I remember it like it was yesterday. My dad transported me and two friends down from Bundaberg and drove around the Gold Coast for the day waiting for us. It was the first Big Day Out after the widely reported ‘last ever’ one in 1997. I remember the day with extreme fondness, mostly for the kindness of the punters. Sure, there was the odd weirdo, but the unspoken rule of looking out for those around you was well in force. (I’ll always be grateful for the kind souls who chose to rescue my naive self from the Marilyn Manson moshpit.) That year, I got to see some of the bands that were dear to my heart at the time — Manson (of course), Korn, Hole, and even Fur and Sean Lennon. While I can’t so my love for all of these acts continues today, there is no doubt that I was there solely for the bands. Look, here I am counting down the last day!

The next few years of Big Day Out attendance continued in the same vein — great bands, with an audience of tens of thousands of people who were there to enjoy music with like-minded folks. Sure, it was often a bit of a stressful day dealing with the portaloos (or holding it in!), the heat and the crowds — particularly for those of us not used to the surf culture of the Coast — but it was a positive experience overall. Similar things can be said of the now-defunct Livid festival. Generally speaking, at that time, no-one bought tickets to music festivals unless they were really into the bands.

Fast forward a few years, and things started to get ugly. Livid had its last hurrah in 2003 (and smaller festivals like Summersault hadn’t been around for years). Great bands were still booked for the Big Day Out (Iggy and the Stooges, PJ Harvey, the White Stripes, the Beastie Boys and Jane’s Addiction, to name a few), but by the mid 2000s something had started to change (and I’m not talking about she-pees). As a small female, I no longer felt entirely safe being in the crowd on my own to watch a band. People were getting peed on, puked on, spat on, groped and punched. Very few punters were looking out for those around them; it was every man/woman for themselves. For many people, the bands seemed to be an added extra included in the ticket price.

I’m not sure it’s a coincidence that things seemed to get a whole lot worse after the 2005 Cronulla riots. At subsequent Big Day Outs, I noticed an increased number of Southern Cross tattoos, Australian flags, and aggressive people asking others to kiss said flag. A friend of mine was abused for daring to wear a temporary tattoo of the Aboriginal flag to the Sydney event on Australia Day. Due to factors such as these, I decided that the 2008 event would be my last. Rage Against the Machine was the last Big Day Out band I ever saw, and I’m glad to have ended it this way. (It is unfortunate, however, that a good number of the shirtless, aggressive, sweaty bogans in the crowd seemed to completely misinterpret the intent of RATM’s music.)

While Livid may have closed shop, in the early 2000s new festivals began to emerge. The most notable was Splendour in the Grass in Byron Bay (which has now relocated to Woodford north of Brisbane). While I attended three of these festivals over the years (twice even camping!), the overcrowding and general ‘yuckiness’ eventually started to permeate there as well. Three days of portaloos and rain and mud and no showering gets to you after a while. In addition, while there are often very high-quality international acts included on the bill, I can’t help but think that the event could (with some careful curating) be condensed into a single day with minimal ‘filler’ — thus eliminating the need to camp, arrange costly accommodation or travel long distances several days in a row.

Smaller festivals also began to pop up in the 2000s, with Laneway expanding to Brisbane in 2007. The first festival (in the alleyway next to the Zoo) was a fabulous experience, with Peter Bjorn and John, Camera Obscura, Yo La Tengo and the Redsunband making for an excellent day out. Sadly, the relaxed atmosphere seemed to have been lost by the second Brisbane event in 2008, with music seemingly not being an important factor for many in attendance. Having been jostled one too many times by Rayban-wearing, fluoro-wearing, talking-over-the-top-of-the-music hipsters, we gave up. It was easier to hear Feist from outside the festival gates than it was inside. Laneway has since relocated to a new venue in Brisbane, but I haven’t ventured back — mostly due to the fact that I recognise very few bands on the lineup (and I’m not one attend a festival if I’m not into the music).

Also emerging around this time was Sunset Sounds in Brisbane, another two-day festival. While, like Splendour, this one could also easily be condensed into a single day, it’s held at the Riverstage in the middle of the city —making it easy to come and go with little hassle. I attended my first Sunset Sounds in 2011 in the pouring rain (literally a few days before the river broke its banks and flooded the city), and was lucky enough to see Joan Jett and the Blackhearts, Public Enemy and Sleigh Bells. The festival took a break in 2012, but according to the website will return for 2013.

The 2000s also saw the emergence of Soundwave, a niche festival aimed at fans of metal and hard rock. I attended my first Soundwave in 2010 (enticed by the opportunity to see Faith No More), and I admit that I wasn’t looking forward to the experience all that much (with the idea of returning to a 50 000-strong festival a little hard to stomach). Soundwave proved to be an overwhelmingly positive experience — enough so that I returned the next year. It became clear that you’d have to be a real fan of the music to spend $160 on a ticket to see this number of ‘heavy’ acts; consequently, most of the punters were respectful, the crowd seemed a little older and wiser, and I even spotted some families enjoying the day together. While I’m not attending the 2012 festival (it’s a little too much of a c.1998–99 nostalgia-fest for me), if I’m into the music on a future lineup I’ll be in attendance.

In 2011, I saw a Facebook post that gave me real hope for the future of festivals. A new event called Harvest was coming, and the organisers had somehow managed to convince Portishead (and a heap of other amazing bands) to play. The tagline was ‘A civilised gathering’ — which sounded like it was aimed squarely at me. There was also this:

Take the line-up of your typical European multi day event, cut out the filler and the acts that everyone has seen once too many times and pack all the greatness into one incredible day for discerning music lovers.

Given that this would likely be my one and only chance to see Portishead live, and that I was promised a ‘civilised gathering’, Harvest excited me. A lot. I’m pleased to say that I wasn’t disappointed. While I understand that the Melbourne event had some teething problems involving drinks tickets (which doesn’t concern me greatly as I prefer sobriety when watching bands so that I can take it all in with clarity), the Brisbane festival delivered everything it had promised. The lineup was full of quality acts (TV on the Radio, the Flaming Lips, the National, Death in Vegas); there was plenty of space between the stages; the portaloos were kept clean; if someone ran into you, they would stop and profusely apologise; and, most importantly, everyone was there for the music. I had the most amazing festival experience of my life right at the front for Portishead (and, yes, this fangirl got to have a brief encounter with the lovely Beth when she left the stage to greet the crowd), and the whole day was stress free. I left the festival that day with the same feeling I had leaving my first Big Day Out in 1999 — one of pure elation, having experienced something special with thousands of people who all understood.

Some people have suggested that my disdain towards the Big Day Out and other festivals could stem from just ‘getting old’. There are a number if reasons why I think that this is untrue. Firstly, I attended my last Big Day Out in my mid 20s — hardly ‘old’ by festival standards, especially since I’d been getting increasingly pissed off with the experience in the years leading up to 2008. Secondly, I have a number of friends who are a decade or more older and stopped attending festivals around the same time. It’s not an age thing; rather, it’s a fed-up-with-idiots-who-couldn’t-give-a-stuff-about-the-music thing.

It’s clear that changes are afoot for the Big Day Out. 2012 marks the first year without co-founder Vivian Lees. The people of Auckland, Adelaide and Perth got a raw deal with much smaller lineups, and Auckland will be completely dropped from the tour after this year. It seems like the perfect opportunity to rethink the approach and start again. Perhaps another hiatus, like the one of 1998, is called for. As it stands, I’d prefer to pay for a plane ticket to see a sideshow in Sydney or Melbourne than venture to the Gold Coast for the day (because, of course, Brisbane sideshows are never prioritised).

For me, the future of music festivals in Australia lies in the Harvests and the Soundwaves — niche festivals aimed at specific markets of music fans. You know, the type of person who would have to actually be a fan of the bands to even consider shelling out $150–200 for a ticket. Whether my dream for the future of Australian festivals will be realised remains to be seen, but I’d prefer to hold onto this hope rather than simply despair for what used to be.

09 April 2011

Iconic buildings of Brisbane: Demolitions in the Joh era (part 3)

Here is the (much delayed) third part to this essay...

Part 3 of 3

‘All we leave behind is the memories’: Demolitions and political protests in the era of Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen

Even marches for International Women’s Day were considered against the law. Women were confronted by the police as they left their forum on 11 February 1978 — they were chanting, ‘You sexist pigs had better start shakin’…Today’s pigs are tomorrow’s bacon’. As a result, forty-nine people were arrested for marching that day; forty-two of them were women. By the time the ban was lifted two years after it had been initiated, more than 2000 people had been arrested.

For most people, participating in these illegal activities was a conscious act of defiance. In addition to street marches being outlawed, so was any kind of demonstration, including distributing leaflets and putting up posters.

Art shows began to pop up around the city, and one of the most remembered of these was the ‘Demolition Show’ of March 1986, held at the Observatory Gallery. The show involved 13 artists who presented a range of works to mark the final exhibition at the Observatory, which was to be demolished, along with several pieces of contemporary art, in April of that year. Artist Lindy Collins stated of her work in the show:

Endnotes

39. L Hurse, interview conducted by email, 2 May 2007.

40. L Finch, ‘DIY defiance: Political posters during the Bjelke-Petersen era (1968–87)’, in L Seear and J Ewington, Brought to Light II: Australian Art 1966–2006, Brisbane, 2006, p.113.

41. ibid, pp.113–14.

42. ibid, pp.113.

43. L Collins, in Demolition Show, Brisbane, 1986.

44. K Ravenswood, ‘Signs of the Times: Political Posters in Queensland’, Eyeline, no.17, summer, 1991, pp.31–32.

Part 3 of 3

‘All we leave behind is the memories’: Demolitions and political protests in the era of Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen

Even marches for International Women’s Day were considered against the law. Women were confronted by the police as they left their forum on 11 February 1978 — they were chanting, ‘You sexist pigs had better start shakin’…Today’s pigs are tomorrow’s bacon’. As a result, forty-nine people were arrested for marching that day; forty-two of them were women. By the time the ban was lifted two years after it had been initiated, more than 2000 people had been arrested.

For most people, participating in these illegal activities was a conscious act of defiance. In addition to street marches being outlawed, so was any kind of demonstration, including distributing leaflets and putting up posters.

They weren’t ‘unlawful’ in inverted commas, they were unlawful, and often deliberately so. The law as enacted and enforced by the Queensland government under Bjelke-Petersen had curtailed democratic rights that had been fought for over a period of many years by unionists, workers, and political organisations. My unlawful actions were a conscious act of defiance in order to win back those democratic rights.(39)Illegal public demonstrations weren’t the only outlets for outraged citizens. The University of Queensland (UQ) became a meeting place for discussions, and Brisbane’s community radio station 4ZZZ, established in 1975 and still operating today, also provided a platform.(40) Screen-printing courses were held, leading to the rise of do-it-yourself posters full of anti-Joh messages. Several printing workshops were established around the city, including Activities at UQ, Craft Press, Griffith Artworks and Black Banana. The posters ranged from crude, hastily produced, stencilled paper to more advanced, meticulously designed art works.(41) Either way, the intention was the same — to publicly denounce Joh Bjelke-Petersen, his government and his actions. Teams would post the prints around the city under the cover of darkness, and they typically didn’t stay up for very long.(42)

Art shows began to pop up around the city, and one of the most remembered of these was the ‘Demolition Show’ of March 1986, held at the Observatory Gallery. The show involved 13 artists who presented a range of works to mark the final exhibition at the Observatory, which was to be demolished, along with several pieces of contemporary art, in April of that year. Artist Lindy Collins stated of her work in the show:

The needs of people in this city are not being thought out carefully. We need areas such as George Street for young artists and galleries to operate in creating a special atmosphere in an otherwise desolate city. As individuals we have no say in the destruction of our city. So far since 1977 in the inner Brisbane city area 24 buildings registered with the national trust have been demolished.(43)Once Joh’s reign was over, a number of exhibitions were held around the country displaying Queensland’s and Australia’s political posters of the era. Just some of the exhibitions included the Earthworks Poster Collective show ‘Political Posters of the ’70s — Work from the Tin Sheds: A Partial Survey’, held at Flinders University Art Museum (1991); ‘Signs of the Times: Political Posters in Queensland’, held at the Queensland Art Gallery (1991); and ‘Hearts and Minds: Australian Political Posters of the 1970s and 1980s’, held at the State Library of New South Wales (1993). These shows served to now legally display some of the posters that for so long were unable to be exhibited. Many of the works were purchased by major galleries and libraries to form a permanent record of the struggles that took place.

‘Signs of the Times’ recognised and gave credit to the fact that political art offers a freedom of community liaison which few other art forms can match — it is one of the few times art really matters on a street level and it is from this position that it derives its potency.(44)Many individuals across Queensland have their own personal reasons for reminiscing about the Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen years. He was regarded by many people, particularly in regional centres, as a Premier who was acting in the best interests of the state. However, to the thousands of Brisbane residents who witnessed first-hand the destruction of heritage buildings and the distress of those arrested whilst trying to do nothing more than have their collective voices heard, he was nothing more than a rogue dictator. No matter which side of the fence an individual wants to sit on, there is no denying that Joh is arguably the most remembered Premier Queensland has ever had. And, one can expect that it will remain that way for many decades to come.

Endnotes

39. L Hurse, interview conducted by email, 2 May 2007.

40. L Finch, ‘DIY defiance: Political posters during the Bjelke-Petersen era (1968–87)’, in L Seear and J Ewington, Brought to Light II: Australian Art 1966–2006, Brisbane, 2006, p.113.

41. ibid, pp.113–14.

42. ibid, pp.113.

43. L Collins, in Demolition Show, Brisbane, 1986.

44. K Ravenswood, ‘Signs of the Times: Political Posters in Queensland’, Eyeline, no.17, summer, 1991, pp.31–32.

24 January 2011

Iconic buildings of Brisbane: Demolitions in the Joh era (part 2)

Part 2 of 3

‘All we leave behind is the memories’: Demolitions and political protests in the era of Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen

The Bellevue Hotel was arguably the most famous of the midnight demolitions (presumably due to the sheer number of people who turned up to watch it fall). However, it is important to remember that most members of the public had no physical or emotional connection to it, since it had been frequented primarily by politicians in its final years standing. On the other hand, Cloudland Ballroom was a venue that had been an important part of the lives of many people of all ages — from those who had attended the ballroom dances of its heyday (some of whom had started romances there), to those of the younger generation who had attended punk music concerts, university examinations and even Sunday markets.(19)

Once again, the Deen Brothers were contracted to demolish the historical landmark, situated in the inner-city suburb of Bowen Hills. Around six months before the demolition took place, the Courier-Mail had reported that Cloudland was for sale, with the speculated asking price being up to $2.5 million. At that time, the La Boite Theatre and Community Arts Network of Queensland was planning a thirties and forties revival ball to bring attention to the fact that the ballroom was under threat. According to organiser Bruce Dickson, the event was taking place ‘…in an effort to remind Brisbane people of the loss that would occur if it was destroyed…In other capital cities you could destroy 50 per cent of the historical buildings overnight and still have much more than we have in Brisbane’.(20) In fact, Cloudland was commonly known around the city as the ‘Social hub of Brisbane’.(21)

Cloudland Ballroom was gone in less than an hour, although the Deen Brothers had expected the job to take a good part of the day. They had moved in with their machinery, as instructed, at 4.00am on 7 November 1982. This time, there were no crowds waiting in protest because very few people had managed to find out about the proposed demolition until it was too late. In fact, the first members of the public to become aware of what was happening were the nearby residents woken by the machinery. ‘“It woke the baby”, Mr Peter Blessing of Boyd Street said. “It’s frightening the way this can take place without any recourse at all. It beats me how they can do it”’.(22)

It wasn’t only the public who weren’t warned of the impending demolition of Cloudland — the state government and the building’s owner had also failed to notify the Brisbane City Council, from whom they required permission in order to legally carry out the demolition.(23) Although Cloudland was not owned by the government (it was owned by real estate promoter Peter Kurts), the media and the public still held Bjelke-Petersen and his Country Party personally responsible for failing to protect Brisbane’s heritage.(24) The maximum fine for demolishing National Trust-listed buildings was $200; the Cloudland penalty was only $125. Clearly, this measly fine was hardly a deterrent for individuals, let alone the state government.(25)

After the demolition of Cloudland, the public made it very clear that they were not happy with what had occurred. People from almost all corners of Brisbane and its surrounds had some kind of connection to the place. An anonymous interviewee stated:

It seems a strange notion that a demolition company could become so well known (if not notorious), that almost everyone in Brisbane could name them. In fact, that is exactly what happened with the Deen Brothers, who were the infamous demolition firm contracted by the state government to demolish heritage-listed buildings up until Joh’s reign as Premier ended. They, along with Joh Bjelke-Petersen, were the target of public outrage when building after building was reduced to rubble.

The five brothers — Happy, Louie, George, Ray and Funny — were proud of their work, despite the outrage constantly directed towards them.(27) In actual fact, the Deen Brothers were simply doing what most of us do every day — their jobs. Being contracted by the state government meant a huge boost in the company’s profits, as well as the added ‘bonus’ of becoming a household name and consequently the most well-known demolition company in Queensland (and perhaps even Australia).

It turns out that the Deens were just as interested and concerned about local heritage as the rest of Brisbane’s residents. Several of them even became ‘tour guides’ in 1991, leading a group of architecture students on heritage walks around the city centre. Students from around Australia had travelled to Brisbane to participate as part of the Biennial Oceanic Architectural Education Conference.(28) The tour concluded at the former site of the Bellevue Hotel, which is now home to a five-storey building constructed by the Bjelke-Petersen government. George stated, ‘…I must admit a few memories come back as I stand here, because this was one of our best jobs’.(29) When asked why the brothers were leading the heritage walk, George answered, ‘We’re on a reconnaissance mission, looking for more sites. No seriously, we believe in preserving heritage too’.(30)

The Deen Brothers’ interest in Brisbane’s lost heritage didn’t stop with a one-off tour around the city. Also in 1991, the state government held an auction for the cast-iron lacework that had been removed from the Bellevue Hotel’s verandas before its demolition. Five pallet loads were sold, including one to George Deen for $400. It was planned that Happy Deen, who was building a house, would use the lacework on the exterior.(31) Since the Bjelke-Petersen era, the Deens have also had a hand in the demolition of other significant buildings in Brisbane, including Festival Hall after it was sold to Devine Limited in 2003.(32)

Public outrage in the Sir Joh era was something that the state government wanted to inhibit at all costs. Up until 1977, street marches and protests had been theoretically a legal right — although, in many cases the police force had been seen to be excessive, as was the case with the Springbok tour. When people began protesting the export of uranium from Queensland ports, Bjelke-Petersen declared that all street marches would be illegal from that point on. Rather than applying through the courts for a march permit, the public would need to apply through the police, who had the authority to grant (or, more accurately, not grant) a permit under the Traffic Act.(33) Joh announced that, ‘Protest groups need not bother applying for permits to stage marches because they won’t be granted’.(34)

People continued to protest illegally, and they were consequently arrested or, worse, bashed by the police. The term ‘police state’ became a reality, as senior police reported directly to the Premier.

Continue to Part 3.

Endnotes

19. A McKenzie, ‘Ballroom became a landmark and more’, Courier-Mail, 8 November 1982.

20. ‘Cloudland for sale if price is right’, Courier-Mail, 30 May 1982.

21. ‘Social hub of Brisbane’, Sunday Sun, 2 October 1977.

22. A McKenzie, ‘Demolishers move in at 4am’, Courier-Mail, 8 November 1982.

23. Fisher, ‘“Nocturnal demolitions”’, p.57.

24. ibid, p.58.

25. ibid.

26. Anonymous, interview conducted by email, 1 May 2007.

27. K Meade, ‘Deens strike again, this time for heritage’, The Australian, 11 July 1981.

28. J Gallagher, ‘The Deens came to town to admire, not to demolish’, Courier-Mail, 11 July 1991.

29. Meade, ‘Deens strike again, this time for heritage’.

30. ibid.

31. ‘George picks up the pieces’, Sunday Sun, 13 August 1991.

32. B Williams, ‘We’re not rubble-rousers, say Deens’, The Courier-Mail, 23 March 2002.

33. R Evans, ‘Right to march movement: King George Square’, in R Evans and C Ferrier, Radical Brisbane: An Unruly History, Melbourne, 2004, p.294.

34. Sunday Mail, 4 September 1977, p.1, quoted in Clare Williamson, ‘Keep in step: The rise of political posters in Brisbane’, Signs of the Times: Political Posters in Queensland, Brisbane, 1991, p.4.

35. Evans, ‘Right to march movement: King George Square’, p.295.

36. L Finch, ‘DIY defiance: Political posters during the Bjelke-Petersen era (1968–87)’, in L Seear and J Ewington, Brought to Light II: Australian Art 1966–2006, Brisbane, 2006, p.113.

‘All we leave behind is the memories’: Demolitions and political protests in the era of Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen

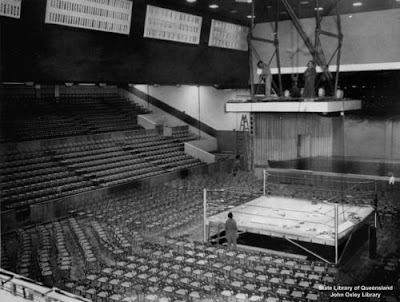

The Bellevue Hotel was arguably the most famous of the midnight demolitions (presumably due to the sheer number of people who turned up to watch it fall). However, it is important to remember that most members of the public had no physical or emotional connection to it, since it had been frequented primarily by politicians in its final years standing. On the other hand, Cloudland Ballroom was a venue that had been an important part of the lives of many people of all ages — from those who had attended the ballroom dances of its heyday (some of whom had started romances there), to those of the younger generation who had attended punk music concerts, university examinations and even Sunday markets.(19)

Image: John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

Once again, the Deen Brothers were contracted to demolish the historical landmark, situated in the inner-city suburb of Bowen Hills. Around six months before the demolition took place, the Courier-Mail had reported that Cloudland was for sale, with the speculated asking price being up to $2.5 million. At that time, the La Boite Theatre and Community Arts Network of Queensland was planning a thirties and forties revival ball to bring attention to the fact that the ballroom was under threat. According to organiser Bruce Dickson, the event was taking place ‘…in an effort to remind Brisbane people of the loss that would occur if it was destroyed…In other capital cities you could destroy 50 per cent of the historical buildings overnight and still have much more than we have in Brisbane’.(20) In fact, Cloudland was commonly known around the city as the ‘Social hub of Brisbane’.(21)

Cloudland Ballroom was gone in less than an hour, although the Deen Brothers had expected the job to take a good part of the day. They had moved in with their machinery, as instructed, at 4.00am on 7 November 1982. This time, there were no crowds waiting in protest because very few people had managed to find out about the proposed demolition until it was too late. In fact, the first members of the public to become aware of what was happening were the nearby residents woken by the machinery. ‘“It woke the baby”, Mr Peter Blessing of Boyd Street said. “It’s frightening the way this can take place without any recourse at all. It beats me how they can do it”’.(22)

It wasn’t only the public who weren’t warned of the impending demolition of Cloudland — the state government and the building’s owner had also failed to notify the Brisbane City Council, from whom they required permission in order to legally carry out the demolition.(23) Although Cloudland was not owned by the government (it was owned by real estate promoter Peter Kurts), the media and the public still held Bjelke-Petersen and his Country Party personally responsible for failing to protect Brisbane’s heritage.(24) The maximum fine for demolishing National Trust-listed buildings was $200; the Cloudland penalty was only $125. Clearly, this measly fine was hardly a deterrent for individuals, let alone the state government.(25)

After the demolition of Cloudland, the public made it very clear that they were not happy with what had occurred. People from almost all corners of Brisbane and its surrounds had some kind of connection to the place. An anonymous interviewee stated:

I heard about Cloudland mostly through my elder siblings. It was also a very visible landmark. Everyone in Brisbane knew of Cloudland (as well as people from Redcliffe where my family lived). Its importance to Brisbane’s musical history was lost because of Joh’s pro-development stance. If Australia and, in this instance, Brisbane, was to develop a non-Indigenous history, it was vital that buildings such as Cloudland and the Bellevue Hotel be kept…We had so very few buildings in the first place that were of historical significance. Now it is all high rise with the few remaining buildings hidden in their shadows. We can only imagine how Cloudland and the other buildings might be considered today if they were still standing.(26)

Image: John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

It seems a strange notion that a demolition company could become so well known (if not notorious), that almost everyone in Brisbane could name them. In fact, that is exactly what happened with the Deen Brothers, who were the infamous demolition firm contracted by the state government to demolish heritage-listed buildings up until Joh’s reign as Premier ended. They, along with Joh Bjelke-Petersen, were the target of public outrage when building after building was reduced to rubble.

The five brothers — Happy, Louie, George, Ray and Funny — were proud of their work, despite the outrage constantly directed towards them.(27) In actual fact, the Deen Brothers were simply doing what most of us do every day — their jobs. Being contracted by the state government meant a huge boost in the company’s profits, as well as the added ‘bonus’ of becoming a household name and consequently the most well-known demolition company in Queensland (and perhaps even Australia).

It turns out that the Deens were just as interested and concerned about local heritage as the rest of Brisbane’s residents. Several of them even became ‘tour guides’ in 1991, leading a group of architecture students on heritage walks around the city centre. Students from around Australia had travelled to Brisbane to participate as part of the Biennial Oceanic Architectural Education Conference.(28) The tour concluded at the former site of the Bellevue Hotel, which is now home to a five-storey building constructed by the Bjelke-Petersen government. George stated, ‘…I must admit a few memories come back as I stand here, because this was one of our best jobs’.(29) When asked why the brothers were leading the heritage walk, George answered, ‘We’re on a reconnaissance mission, looking for more sites. No seriously, we believe in preserving heritage too’.(30)

The Deen Brothers’ interest in Brisbane’s lost heritage didn’t stop with a one-off tour around the city. Also in 1991, the state government held an auction for the cast-iron lacework that had been removed from the Bellevue Hotel’s verandas before its demolition. Five pallet loads were sold, including one to George Deen for $400. It was planned that Happy Deen, who was building a house, would use the lacework on the exterior.(31) Since the Bjelke-Petersen era, the Deens have also had a hand in the demolition of other significant buildings in Brisbane, including Festival Hall after it was sold to Devine Limited in 2003.(32)

Public outrage in the Sir Joh era was something that the state government wanted to inhibit at all costs. Up until 1977, street marches and protests had been theoretically a legal right — although, in many cases the police force had been seen to be excessive, as was the case with the Springbok tour. When people began protesting the export of uranium from Queensland ports, Bjelke-Petersen declared that all street marches would be illegal from that point on. Rather than applying through the courts for a march permit, the public would need to apply through the police, who had the authority to grant (or, more accurately, not grant) a permit under the Traffic Act.(33) Joh announced that, ‘Protest groups need not bother applying for permits to stage marches because they won’t be granted’.(34)

People continued to protest illegally, and they were consequently arrested or, worse, bashed by the police. The term ‘police state’ became a reality, as senior police reported directly to the Premier.

…they knew I was always rock solid behind them and they reported to me who were the students of the university who were giving all the trouble…just as they did in the SEQEB electricity strike, everybody came to me for general direction.(35)Shortly after protesting had been outlawed, in October 1977 one march resulted in a total of 662 people being arrested.(36)

Continue to Part 3.

Endnotes

19. A McKenzie, ‘Ballroom became a landmark and more’, Courier-Mail, 8 November 1982.

20. ‘Cloudland for sale if price is right’, Courier-Mail, 30 May 1982.

21. ‘Social hub of Brisbane’, Sunday Sun, 2 October 1977.

22. A McKenzie, ‘Demolishers move in at 4am’, Courier-Mail, 8 November 1982.

23. Fisher, ‘“Nocturnal demolitions”’, p.57.

24. ibid, p.58.

25. ibid.

26. Anonymous, interview conducted by email, 1 May 2007.

27. K Meade, ‘Deens strike again, this time for heritage’, The Australian, 11 July 1981.

28. J Gallagher, ‘The Deens came to town to admire, not to demolish’, Courier-Mail, 11 July 1991.

29. Meade, ‘Deens strike again, this time for heritage’.

30. ibid.

31. ‘George picks up the pieces’, Sunday Sun, 13 August 1991.

32. B Williams, ‘We’re not rubble-rousers, say Deens’, The Courier-Mail, 23 March 2002.

33. R Evans, ‘Right to march movement: King George Square’, in R Evans and C Ferrier, Radical Brisbane: An Unruly History, Melbourne, 2004, p.294.

34. Sunday Mail, 4 September 1977, p.1, quoted in Clare Williamson, ‘Keep in step: The rise of political posters in Brisbane’, Signs of the Times: Political Posters in Queensland, Brisbane, 1991, p.4.

35. Evans, ‘Right to march movement: King George Square’, p.295.

36. L Finch, ‘DIY defiance: Political posters during the Bjelke-Petersen era (1968–87)’, in L Seear and J Ewington, Brought to Light II: Australian Art 1966–2006, Brisbane, 2006, p.113.

18 January 2011

Baked Relief: Un-feminist, or just welcome help?

Many of you will be aware of the Baked Relief effort happening post-flood in south-east Queensland (which I have been participating in myself). While most are praising the efforts of the bakers contributing to the cause, a minority on Twitter have labelled the movement as 'un-feminist', and accused the volunteers of clogging up the roads with their cars trying to deliver the food.

This has me pretty pissed off, to put it mildly. I consider myself to be a feminist. Yeah, I like to bake stuff and do the occasional bit of sewing, but that has nothing to do with being 'un-feminist' in nature. I bake because I like food, and I sew to avoid contributing to the exploitation of women and children in the garment manufacturing business around the world. Not only that, but my husband helped with the Baked Relief effort - what the hell does that make him?!

Contrary to popular opinion, Baked Relief does not simply consist of 'kept women' fucking around in their kitchens to make ourselves feel better. Many of us live in unaffected suburbs and either don't know someone directly to help with the grunt work, or can't get to an affected suburb to assist. Some of us CAN'T assist for whatever reason (such as physical disability, or children to look after). A good number of us are men (including a colleague of mine), but, yeah, I guess most of us are women. So fucking what?! Clearly the food has been VERY much appreciated, and continues to be. The fact is that the people working so unbelieveably hard out in the sun NEED to be fed and watered. Who else is going to do it if we don't lend a hand?

The Baked Relief team seems to consist of a diverse range of people. There are the stay-at-home mums making a wonderful contribution to the cause, as well as professionals who've been unable to get to their usual place of work. From what I've seen, there are publishing professionals like myself (and Kelley from Peppermint magazine), marketing and PR professionals, IT professionals, and I'm sure many others that I'm not aware of.

My personal situation is that I've been told I can not yet return to work. I do, however, have some work I can complete from home. So, in between jobs, I've been cooking up a storm for Baked Relief. I have not been clogging up the roads to deliver my baked goods - I have either delivered to a mass drop-off point like Black Pearl Epicure in Fortitude Valley, or my goods have been collected by someone doing the rounds of the city. Most of us have been combining our efforts in order to deliver as much food at one time as possible, but also ensure that less cars are out there on the roads.

Baked Relief is not about women saying that they can't get out there and shovel mud and push a gurney. It's about a large group of people making a big difference to the lives of others in their own way. They should not be criticised for what they are doing, they should be congratulated.

I'm pretty sure I'll be doing my fair share of dirty work when I can get back into the office later this week, and until then I'll continue to bake along with the wonderful people who started and continue the Baked Relief movement.

30 October 2010

Iconic buildings of Brisbane: Festival Hall

Last night I was having an interesting conversation on Brisbane's history with tearing down iconic buildings (often under the cover of darkness during the Joh Bjelke-Petersen era, with the help of the Deen Brothers). Over the years I've explored the history of Brisbane's buildings a little bit, so I wanted to share one with you here about Festival Hall.

Unlike the buildings torn down during the reign of Joh, Festival Hall disappeared only a few years ago from the city centre. When I began my research for this particular essay, I interviewed some locals who had connections to the venue. I expected to find that people would be far more opposed to the demolition of the building, but, as you will read, most instead felt that the 'atmosphere' of Festival Hall could exist elsewhere, and it wasn't the building itself that mattered so much.

This essay was written in 2005, and will be presented in two parts. Full references will be given at the end of part two. The appendix refers to interviews that I conducted at the time.

Part 1 of 2

‘It alters your DNA somehow, seeing music like that…’

Unlike the buildings torn down during the reign of Joh, Festival Hall disappeared only a few years ago from the city centre. When I began my research for this particular essay, I interviewed some locals who had connections to the venue. I expected to find that people would be far more opposed to the demolition of the building, but, as you will read, most instead felt that the 'atmosphere' of Festival Hall could exist elsewhere, and it wasn't the building itself that mattered so much.

This essay was written in 2005, and will be presented in two parts. Full references will be given at the end of part two. The appendix refers to interviews that I conducted at the time.

Part 1 of 2

‘It alters your DNA somehow, seeing music like that…’

(Brad Shepherd, interviewed by Noel Mengel in the Courier-Mail 9 August 2003, on seeing Slade at Festival Hall in 1974)

Introduction

Introduction

Way back on April 27 1959, Brisbane received what some would call an extraordinary gift — a £300 000 hall that was, in the opinion of journalists, ‘an outstanding example of modern architecture and engineering’ (Courier-Mail, 1959, p. unknown). The development of this new multi-purpose entertainment venue ensured that Brisbane did not fall short of the rest of the country when it came to seeing big-name musical acts. Had it not been for Festival Hall, Brisbane residents may have been bypassed by the likes of Led Zeppelin, the Beatles, Morrissey, Nirvana, and even Cinderella on Ice in the decades that followed. And, although by the 1980s and ’90s venues of comparable capacity were being established in the region, no new building could undo the rich cultural history surrounding that of the ‘original’. However, to use a common cliché, ‘all good things must come to an end’. The public culture site that was Festival Hall is currently in a state of corporate culture — that is, the Devine industrial corporation now controls the land on which the building once stood. Eventually, the upper class will inhabit the new high-rise apartments in a complete reversal of the site — from public culture to high culture.

Image: John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

Festival Hall: The building

The construction of Festival Hall was distinctly modern in what it signified for the people of the Brisbane region. Originally home to a stadium used exclusively for boxing — consisting of not much more than a ‘ringside, outer ringside and bleachers’ (Telegraph, 1959, p.39) — the site on which Festival Hall was built symbolised that Brisbane was progressing. Although it would still house boxing matches (boasting a £2000 American-style ring first imported for the 1956 Olympic Games in Melbourne), the new Festival Hall consisted of a stage (large enough to accommodate 120 musicians), an orchestral pit, and ‘modern’ facilities for both the general public and the boxers, artists and musicians.

The general feeling towards this new development was that it would put Brisbane ‘up there with the rest of them’ in terms of the live music entertainment circuit. It would unleash unprecedented possibilities for the general public to experience not only classical music, but international performers of popular music. This development also meant that the economy of Brisbane would grow, with countless jobs created as both a direct and indirect result of Festival Hall’s construction.

The residents of Brisbane were proud of their new entertainment centre, and they were equally proud of its visual appeal. French grey glazed tiles, lime-coloured zincaneal awnings, a marble chip terrazzo and textured brick work were some of the modern features contributing to Festival Hall’s aesthetic appeal (Telegraph, 1959, p.40), One of the most obvious modern features of the Hall was its 6000 seating capacity. By employing this manner of seating for patrons, audience members became individuated subjects. That is, although there could be up to 6000 people in the Hall at any given time, each audience member was separate in themselves and positioned in an individual manner — by their designated section, row and seat number. This culturally regimented system is one that was employed in the Hall until its destruction. Of course, there were times when the floor area of Festival Hall was transformed into a more communal space, when it was a general admission standing area or dance floor for certain popular music events (from about the 1970s onwards). Although audience members remained individuated subjects by their own personal experiences in the collective environment, the obvious physical barriers had been removed.

It was only during the 1970s that Festival Hall’s architecture really started to come ‘alive’. That is, it developed its own distinctive character. As described by an anonymous interviewee, ‘As the years rolled on, it became dirtier, smellier and more “rock”’. Had it not become a haven for witnessing rock acts such as Led Zeppelin and the like, Festival Hall is likely to have remained a ‘clean’ and sterile venue devoid of any ‘real’ atmosphere, and its architecture, although distinctly state-of-the-art for the 1950s, would simply have dated. Instead, the Hall captured a little bit of essence from each of the performances that were held there — from the worn seats, cracked brick work and musty smells to the scuffs on the stage and holes in the dressing room walls. As if almost by accident (and as a direct result of the collective experiences of the bands and patrons), Festival Hall became a grungy, dirty rock venue — the way they all should be, of course.

It was only during the 1970s that Festival Hall’s architecture really started to come ‘alive’. That is, it developed its own distinctive character. As described by an anonymous interviewee, ‘As the years rolled on, it became dirtier, smellier and more “rock”’. Had it not become a haven for witnessing rock acts such as Led Zeppelin and the like, Festival Hall is likely to have remained a ‘clean’ and sterile venue devoid of any ‘real’ atmosphere, and its architecture, although distinctly state-of-the-art for the 1950s, would simply have dated. Instead, the Hall captured a little bit of essence from each of the performances that were held there — from the worn seats, cracked brick work and musty smells to the scuffs on the stage and holes in the dressing room walls. As if almost by accident (and as a direct result of the collective experiences of the bands and patrons), Festival Hall became a grungy, dirty rock venue — the way they all should be, of course.

Image: John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

Festival Hall: The public culture site

Like many modern sites, Festival Hall had a contradictory nature about it as well. While it was a symbol that Brisbane was progressing as a city, many bands that played there over the years were those who stood against precisely that form of industrial progress and the ‘loss of human “spirit”’. This type of progress — that of the rich getting richer and the poor, essentially, getting poorer — was critiqued by numerous performers who are widely known for their lyrics conveying anti-capitalist ideas, such as Michael Franti, Midnight Oil, the Ramones, U2 and Ben Harper. To many of these bands, industrial progress would inevitably lead society to the point of self-destruction and the loss of the individual. By visiting this symbol of progress and filling it with their anti-corporate, anti-establishment messages, they were indeed contributing to the contradictory nature of modernity. Furthermore, this was then inverted once again by the selling of T-shirts and other merchandise at a premium price in the foyer.

By Festival Hall acting as a representation of the contradictory nature of modernity, it was supplying a site of resistance — a place for ‘human subjects to make their mark’. (De Certeau, 1985, p.136) ‘[Michel de Certeau] sees the site of human subject formation at those points where resistance and play occur, where the characteristics of the human subject are not to function within a system, but to deflect and to resist functionality through counter-practices of nonconformity.’ Therefore, according to de Certeau’s model, audience members at Festival Hall were participating in an act which conveyed messages of anti-progress and promoted individuality (which could be somewhat achieved by the creation of individuated spaces within the communal environment). Likewise, visiting performers were actively participating in this site of resistance by playing at the venue (with its symbolic representation of industrial progress), and thereby contributing to the local Brisbane economy.

By providing a central space in the heart of the city where literally thousands of people could gather, Festival Hall was clearly a public space (although, as discussed, it also had elements of corporate and industrial culture associated with it). Like many other cultural sites, Festival Hall contained a number of individual spaces within the public space itself. Of course, each individuated member of the audience came together to form the spectorial space, whereby each person is in the Hall witnessing the one cultural event (occurring in front of them on the stage). At the same time, audiences members could identify as members of specific groups — whether they be class related or connected to their musical preferences — resulting in a social space being created temporarily. In addition, an economic space was also created (both in and around the Hall) — via the exchange of money for entry or tickets, the wages paid to ushers and other employees, and the economic benefit reaped by surrounding businesses before and after the events (particularly clubs, bars, restaurants, public transport and taxi services).

James Donald discusses Simmel’s inference that ‘the metropolitan mentality is not a question of the self-creative versus the blasé, nor the individual versus the social’ (Donald, 1995, p.81). In other words, metropolitan sites such as Festival Hall are not simply about corporate power, nor are they simply about existing as a socially interactive environment. ‘He does not see in the metropolis only the manifestation of a power that oppresses the individual. Rather, he suggests how agency is here enacted with the field of possibilities defined by this environment: its space, its population, its technologies, its symbolisations. The city is the way we moderns live and act, as much as where’ (Donald, 1995, p.81). These public spaces present a range of possibilities that are determined by the building itself, its location, its surrounding features, and the way in which humans co-inhabit that space.

Image: John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)