Unlike the buildings torn down during the reign of Joh, Festival Hall disappeared only a few years ago from the city centre. When I began my research for this particular essay, I interviewed some locals who had connections to the venue. I expected to find that people would be far more opposed to the demolition of the building, but, as you will read, most instead felt that the 'atmosphere' of Festival Hall could exist elsewhere, and it wasn't the building itself that mattered so much.

This essay was written in 2005, and will be presented in two parts. Full references will be given at the end of part two. The appendix refers to interviews that I conducted at the time.

Part 1 of 2

‘It alters your DNA somehow, seeing music like that…’

(Brad Shepherd, interviewed by Noel Mengel in the Courier-Mail 9 August 2003, on seeing Slade at Festival Hall in 1974)

Introduction

Introduction

Way back on April 27 1959, Brisbane received what some would call an extraordinary gift — a £300 000 hall that was, in the opinion of journalists, ‘an outstanding example of modern architecture and engineering’ (Courier-Mail, 1959, p. unknown). The development of this new multi-purpose entertainment venue ensured that Brisbane did not fall short of the rest of the country when it came to seeing big-name musical acts. Had it not been for Festival Hall, Brisbane residents may have been bypassed by the likes of Led Zeppelin, the Beatles, Morrissey, Nirvana, and even Cinderella on Ice in the decades that followed. And, although by the 1980s and ’90s venues of comparable capacity were being established in the region, no new building could undo the rich cultural history surrounding that of the ‘original’. However, to use a common cliché, ‘all good things must come to an end’. The public culture site that was Festival Hall is currently in a state of corporate culture — that is, the Devine industrial corporation now controls the land on which the building once stood. Eventually, the upper class will inhabit the new high-rise apartments in a complete reversal of the site — from public culture to high culture.

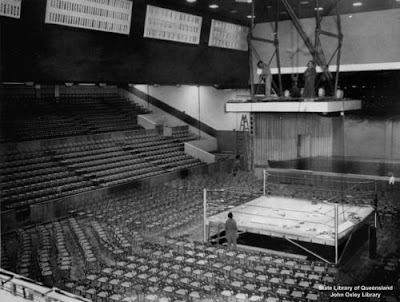

Image: John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

Festival Hall: The building

The construction of Festival Hall was distinctly modern in what it signified for the people of the Brisbane region. Originally home to a stadium used exclusively for boxing — consisting of not much more than a ‘ringside, outer ringside and bleachers’ (Telegraph, 1959, p.39) — the site on which Festival Hall was built symbolised that Brisbane was progressing. Although it would still house boxing matches (boasting a £2000 American-style ring first imported for the 1956 Olympic Games in Melbourne), the new Festival Hall consisted of a stage (large enough to accommodate 120 musicians), an orchestral pit, and ‘modern’ facilities for both the general public and the boxers, artists and musicians.

The general feeling towards this new development was that it would put Brisbane ‘up there with the rest of them’ in terms of the live music entertainment circuit. It would unleash unprecedented possibilities for the general public to experience not only classical music, but international performers of popular music. This development also meant that the economy of Brisbane would grow, with countless jobs created as both a direct and indirect result of Festival Hall’s construction.

The residents of Brisbane were proud of their new entertainment centre, and they were equally proud of its visual appeal. French grey glazed tiles, lime-coloured zincaneal awnings, a marble chip terrazzo and textured brick work were some of the modern features contributing to Festival Hall’s aesthetic appeal (Telegraph, 1959, p.40), One of the most obvious modern features of the Hall was its 6000 seating capacity. By employing this manner of seating for patrons, audience members became individuated subjects. That is, although there could be up to 6000 people in the Hall at any given time, each audience member was separate in themselves and positioned in an individual manner — by their designated section, row and seat number. This culturally regimented system is one that was employed in the Hall until its destruction. Of course, there were times when the floor area of Festival Hall was transformed into a more communal space, when it was a general admission standing area or dance floor for certain popular music events (from about the 1970s onwards). Although audience members remained individuated subjects by their own personal experiences in the collective environment, the obvious physical barriers had been removed.

It was only during the 1970s that Festival Hall’s architecture really started to come ‘alive’. That is, it developed its own distinctive character. As described by an anonymous interviewee, ‘As the years rolled on, it became dirtier, smellier and more “rock”’. Had it not become a haven for witnessing rock acts such as Led Zeppelin and the like, Festival Hall is likely to have remained a ‘clean’ and sterile venue devoid of any ‘real’ atmosphere, and its architecture, although distinctly state-of-the-art for the 1950s, would simply have dated. Instead, the Hall captured a little bit of essence from each of the performances that were held there — from the worn seats, cracked brick work and musty smells to the scuffs on the stage and holes in the dressing room walls. As if almost by accident (and as a direct result of the collective experiences of the bands and patrons), Festival Hall became a grungy, dirty rock venue — the way they all should be, of course.

It was only during the 1970s that Festival Hall’s architecture really started to come ‘alive’. That is, it developed its own distinctive character. As described by an anonymous interviewee, ‘As the years rolled on, it became dirtier, smellier and more “rock”’. Had it not become a haven for witnessing rock acts such as Led Zeppelin and the like, Festival Hall is likely to have remained a ‘clean’ and sterile venue devoid of any ‘real’ atmosphere, and its architecture, although distinctly state-of-the-art for the 1950s, would simply have dated. Instead, the Hall captured a little bit of essence from each of the performances that were held there — from the worn seats, cracked brick work and musty smells to the scuffs on the stage and holes in the dressing room walls. As if almost by accident (and as a direct result of the collective experiences of the bands and patrons), Festival Hall became a grungy, dirty rock venue — the way they all should be, of course.

Image: John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

Festival Hall: The public culture site

Like many modern sites, Festival Hall had a contradictory nature about it as well. While it was a symbol that Brisbane was progressing as a city, many bands that played there over the years were those who stood against precisely that form of industrial progress and the ‘loss of human “spirit”’. This type of progress — that of the rich getting richer and the poor, essentially, getting poorer — was critiqued by numerous performers who are widely known for their lyrics conveying anti-capitalist ideas, such as Michael Franti, Midnight Oil, the Ramones, U2 and Ben Harper. To many of these bands, industrial progress would inevitably lead society to the point of self-destruction and the loss of the individual. By visiting this symbol of progress and filling it with their anti-corporate, anti-establishment messages, they were indeed contributing to the contradictory nature of modernity. Furthermore, this was then inverted once again by the selling of T-shirts and other merchandise at a premium price in the foyer.

By Festival Hall acting as a representation of the contradictory nature of modernity, it was supplying a site of resistance — a place for ‘human subjects to make their mark’. (De Certeau, 1985, p.136) ‘[Michel de Certeau] sees the site of human subject formation at those points where resistance and play occur, where the characteristics of the human subject are not to function within a system, but to deflect and to resist functionality through counter-practices of nonconformity.’ Therefore, according to de Certeau’s model, audience members at Festival Hall were participating in an act which conveyed messages of anti-progress and promoted individuality (which could be somewhat achieved by the creation of individuated spaces within the communal environment). Likewise, visiting performers were actively participating in this site of resistance by playing at the venue (with its symbolic representation of industrial progress), and thereby contributing to the local Brisbane economy.

By providing a central space in the heart of the city where literally thousands of people could gather, Festival Hall was clearly a public space (although, as discussed, it also had elements of corporate and industrial culture associated with it). Like many other cultural sites, Festival Hall contained a number of individual spaces within the public space itself. Of course, each individuated member of the audience came together to form the spectorial space, whereby each person is in the Hall witnessing the one cultural event (occurring in front of them on the stage). At the same time, audiences members could identify as members of specific groups — whether they be class related or connected to their musical preferences — resulting in a social space being created temporarily. In addition, an economic space was also created (both in and around the Hall) — via the exchange of money for entry or tickets, the wages paid to ushers and other employees, and the economic benefit reaped by surrounding businesses before and after the events (particularly clubs, bars, restaurants, public transport and taxi services).

James Donald discusses Simmel’s inference that ‘the metropolitan mentality is not a question of the self-creative versus the blasé, nor the individual versus the social’ (Donald, 1995, p.81). In other words, metropolitan sites such as Festival Hall are not simply about corporate power, nor are they simply about existing as a socially interactive environment. ‘He does not see in the metropolis only the manifestation of a power that oppresses the individual. Rather, he suggests how agency is here enacted with the field of possibilities defined by this environment: its space, its population, its technologies, its symbolisations. The city is the way we moderns live and act, as much as where’ (Donald, 1995, p.81). These public spaces present a range of possibilities that are determined by the building itself, its location, its surrounding features, and the way in which humans co-inhabit that space.

Image: John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

.jpg)